By Eloi Laurent, Senior Economist and Professor at the Sciences Po Centre for Economic Research (OFCE)

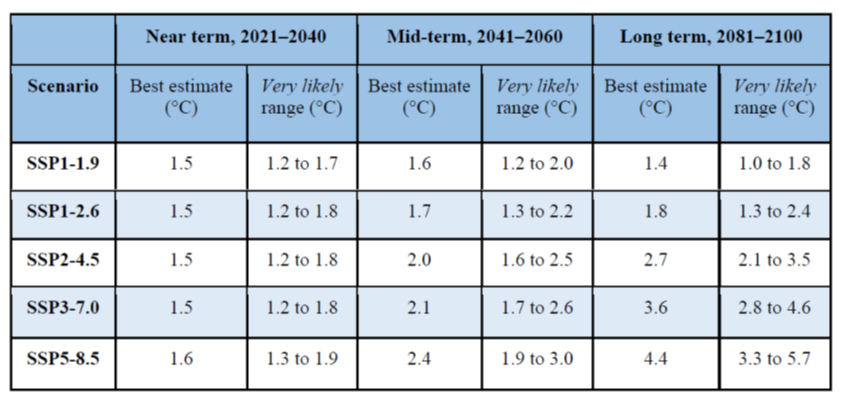

There is a shattering table on page 18 of the Summary for Policymakers of the Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report by the IPCC released last month. Its second column shows that all of the five main climate scenarios considered converge toward a 1.5 C degrees world at more or less rapid pace. Call it the column of fear.

In the same table, the third line shows that one climate scenario dubbed “SSP1-1.9” foresees a stabilization of global warming at 1.6 degrees between 2041–2060 before witnessing a decrease to 1.4 degrees at the end of the 21st century. Call it the line of hope. To be honest, the only thing that mattered to me when I saw this table among the thousands of pages of the IPCC Report was: what is SSP1? And how do we get there?

SSP 1 stands for “Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 1” and it’s one of the five climate narratives that the IPCC now uses to describe interactions between social dynamics and biophysical realities that will determine the climate future of human communities around the globe. These five scenarios have been detailed in a 2017 paper which has this to say about SSP 1: “The world shifts gradually, but pervasively, toward a more sustainable path, emphasizing more inclusive development that respects perceived environmental boundaries. Management of the global commons slowly improves, educational and health investments accelerate the demographic transition, and the emphasis on economic growth shifts toward a broader emphasis on human well-being. Driven by an increasing commitment to achieving development goals, inequality is reduced both across and within countries. Consumption is oriented toward low material growth and lower resource and energy intensity.”

In other words, moving beyond economic growth and toward human well-being is a critical necessity for the future of humanity. The Wellbeing Economy Alliance is committed to doing just that. My understanding of our common commitment is that the age of “indicators” is behind us: we now need to work on well-being policies, i.e. operationalizing new visions of the economy and mainstreaming these visions into policies. More precisely, we need both new narratives and visions on the one hand and new institutions and policies on the other. It can be said indeed that transitions are about turning aspirations into institutions.

An important resource in this perspective is the WEAll’s Policy Design Guide released last March, which has inspired me to offer a new class in my home university, Sciences Po, and more precisely within the Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA). The class is called “Building well-being policies” and has been offered for its first iteration to a group of 21 students in the Master program starting in September 2021. The undeniable strength of PSIA is its global fabric, with 1500 students representing over 110 countries. In the class, 21 students representing 11 nationalities are being asked to build their own well–being vision and policy, with the WEAll’s Policy Design Guide as a compass. The main assignment for the class is a 15-pages long fully-fledged proposal of well-being policy.

After the introductory session devoted to the course’s purpose, outline and organization, the class has really started (“Part I: The Well-being Transition: Connecting Well-being to Sustainability”) with a session devoted to “Building your well-being policy: design thinking and tools” divided in two parts: a presentation/illustration of key building blocks of well-being policies (narratives; frameworks; concepts; metrics; participation; institutions) and a general discussion of the Policy Design Guide (see below).

Session 3 and Session 4 are devoted to presenting one possible well-being policy narrative and vision, the instructor’s, insisting in turn on two critical nodes in the social-ecological feedback loop: the health-sustainability nexus (of “full health” nexus) and the sustainability-justice nexus.

Sessions 5 to 8 (“Part II: Understanding, measuring and improving well-being and sustainability”) will be devoted to reviewing main well-being dimensions’ theoretical underpinning and empirical evidence, from the elementary dimensions of economic well-being (employment and income), to widening the lens to human development to putting well-being in motion with resilience and sustainability.

“Part III: Building Well-being Policies around the world at all levels of governance”, with Sessions 9 to 11, is meant to show students that the well-being transition is already under way across the globe at different governance levels, from the European Union to Bhutan, New Zealand, Iceland and Finland to local initiatives such as Amsterdam City Doughnut and BrusselsDonut. The class concludes with a Well-being Policies Forum where students have 5 minutes to present their final paper in poster session format.

To my knowledge, this class is the first to use WEAll’s Policy Design Guide and showcase the WEGo’s patient and precious work. A widespread WEALL curriculum would be a key asset to achieving the well-being shift we so direly need.

What some PSIA students have to say about WEAll’s Policy Design Guide

Main strengths

“The Policy Design Guide was very comprehensive and helpful in gaining tangible skills to build well-being policies. Policies are not a “one-size-fits-all” so I think the inherent nature of the guide is helpful in pointing policy-makers and citizens in the right direction to create and/or lobby for well-developed, inclusive well-being policies.”

“The Design-Guide is very eye-catching which makes it interesting to read. I think it was a great idea to include definitions for key-words and phrases in the guide. This establishes greater clarity and encourages the reader to keep reading. Additionally, including the “purpose,” “how to,” and tips for each step on how to achieve the purpose is a great way to interact with the reader, keep them engaged, and, again, establish clarity.”

“In my opinion, the guide is a really useful tool to help citizens and governments to design and correctly implement well-being visions and transitions, since it is very much detailed and reports a lot of best-case practical examples.”

“I particularly liked the transition boxes from ‘Old Economic Policies’ to ‘Wellbeing Economy Policies’. They helped the transition in thought process – especially for someone who has been working/studying policies before from an ‘old economic’ perspective.”

Possible improvements

“I found it sometimes to be redundant, especially about the citizens’ co-participation- which is of course paramount for successful implementation of a well being policy, but I think it was reported too many times. Also, I would suggest to use also developing countries more often as best-practice examples of well-being initiatives, by showing that market-led economic growth is not the only possible step of development for this kind of countries. Finally, I would further suggest to show graphically, in a more accurate way, the difference between the old economic policy and the new one.”

“I think that the guide needs additional arguments, why one should implement well-being policies. I have the feeling that, e.g., Ukrainian officials or politicians thinking about a public endorsement would be reluctant to conduct a significant shift without tangible examples of why to bother (or, as may media claim, “spend tax-payers money”). So some case success stories or maybe methodology to convince conservative state systems would be an asset.”

“While the booklet did not resemble a typical guide, including ‘guide’ in the title may be slightly confusing. From my understanding, it is meant to initiate the thought process in wellbeing economy policies (transition from old to wellbeing and tips), and encourage a platform/starting point from which to work further.”

“While speaking about building a well-being policy in a particular field, an explanation/additional info would help to understand how people may adopt strategies in specific sectors with regard to the whole socioeconomic system and its problems: how to deal with some challenges (e.g. poverty) and how (if needed) apply effects of well-being policy in one field to an entire system.”

the discussion?

Let us know what

you would like

to write about!