by: Erinch Sahan

A fundamental change is sweeping across the business world. Big ideas are spreading, new slogans being echoed, and the very purpose of business being questioned. A host of concepts and initiatives are driving this conversation. From BCorps to Social Enterprise, Cooperatives to Shared Value, the market-place of ideas is heating up.

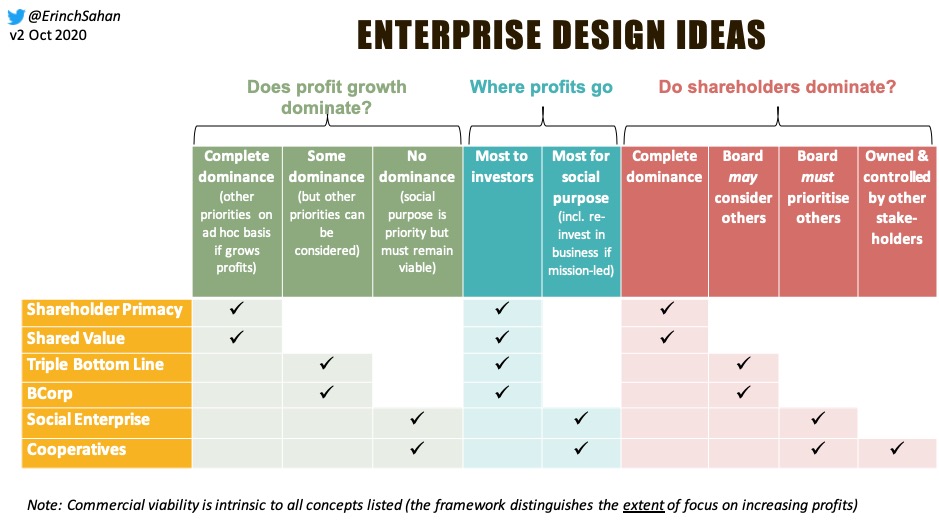

These are all, by-and-large, positive developments. But how do these enterprise design ideas compare? Here’s an attempt to compare their essential structural features and assess the extent to which shareholder dominance and profit primacy remain embedded in enterprise design. In other words, the framework below compares the minimum in structural design that is required by these concepts.

It’s worth noting that we are comparing a mixture of legal forms, certifications and management concepts. For instance, many jurisdictions allow legal registration as a Cooperative, Social Enterprise or Benefit Corporation. Others are certifications to validate claims of being a Social Enterprise or BCorp. Meanwhile, new concepts like Shared Value or Triple Bottom Line are infiltrating MBA programmes, to guide a new generation of corporate leaders. They all (at least implicitly) deviate from shareholder primacy.

Turning away from Friedman? The answer lies in enterprise design.

In 1970, Milton Friedman penned, in the New York Times Magazine, the article ‘The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits’. While proclaiming this today would seem short-sighted (and a public relations own-goal), it is an honest account of shareholder primacy. This remains baked into the DNA of most companies – a persistent straight-jacket that most executives must wear.

The economic imagination has since moved away from this singular obsession with profits for shareholders as the exclusive purpose of business. But enterprise design hasn’t.

While trapped in shareholder primacy, a growing chorus of business leaders declare their discovery of enlightened self-interest, where their long-term profitability relies on being socially responsible. Inconvenient trade-offs are swept aside and questioning how profits are shared remains taboo (the largest shareholders always get the biggest dividend cheques). Yet, some executives pronounce that the purpose of their company is ‘people and planet before profits’ – a far cry from Friedman’s doctrine and the prevailing corporate model that financial markets hold firmly in place. Nonetheless, the narrative has moved, substantially.

How the narrative has shifted

This means enterprise design has become central as we explore purpose and impact. It has crept up on us all. It probably started a few decades ago, with new corporate goals like minimising or eliminating the worst harms of corporate behaviour (usually where a PR-disaster beckoned). Think sweatshops and poisoned rivers. It then evolved to focus on broader social and environmental impacts: human rights impact assessments, environmental impact reports, or indicators for how a business impacts sustainable development. This focus on impact largely happened over the last decade.

But positive impact requires practices and investments that actively foster it. Without inclusive trading partnerships, workers in supply chains remain trapped in poverty wages and precarious employment. Without investment into water-treatment plants, local rivers remain polluted. Under shareholder primacy, if the cost-benefit analysis doesn’t add-up, people and planet take a back-seat (unless regulated by government).

To embrace ‘purpose’, a business must be designed to prioritise such investments and practices.

This means enterprise designs that allow objectives other than profit growth to be a priority, and to give voice and power to stakeholders other than shareholders. Otherwise, doing good is only possible where it grows profits.

A note here to not confuse profit maximisation with commercial viability. Staying in business is necessary for all businesses. Continuously growing profits isn’t.

Pursuing purpose while in a straight-jacket

The enthusiasm for corporate purpose is evidence that we are joining the right dots. However, unless business is designed to focus on people and planet, it chases ever more profits and ignores social and environmental impacts, where the financial rewards don’t suffice. And it is enterprise design that can unlock the practices and impacts that we all agree business must embrace.

Expectations of dividend growth and boards full of shareholder representatives lock-in the shareholder primacy design. This dominant structure ensures a focus on always increasing profits, and forces extraction of profits for the purpose of growing shareholder wealth. It’s a straight-jacket, within which inclusive and truly sustainable corporate culture is held in check, often relegated to projects and initiatives that don’t threaten the pursuit of growing profits.

All businesses need to be profitable, but it’s the focus on maximising or growing profits that holds back authentic corporate purpose. Whether an enterprise is designed to deviate from this paradigm is the central question.

In recognition, an increasing number of businesses are claiming to possess a more evolved design. But how can we know if a business is truly designed to put people and planet before (or alongside) profit? Ideas and movements like Social Enterprise, Triple Bottom Line, BCorp, Shared Value and Cooperatives are attempting to give the answer.

People, Planet & Profit: how far do ideas really go?

While on paternity leave, I’ve had some headspace to grapple with how enterprise design ideas compare. I threw up on Twitter some thoughts, and a discussion unfolded (see thread here):

What emerged is a framework that helps draw key distinctions between concepts like BCorp and Social Enterprise. The focus is on the most fundamental and structural features that determine enterprise design.

Based on my analysis, I believe the following claims are the best way to describe the concepts, certifications and legal forms assessed:

- Shareholder Primacy: Only Profit Matters

- Shared Value: People and Planet, if it Helps Profit

- Triple Bottom Line and BCorp: People and Planet without undermining Profit

- Social Enterprise and Cooperatives: People and Planet before Profit

There are nuances missing and exceptions within each category. A business with a shareholder primacy structure may be majority controlled by an altruistic shareholder, who uses their power to ensure it behaves like a social enterprise. I don’t account for such optional benevolent use of power. In cooperatives, members (therefore power-holders) could be an already empowered stakeholder (e.g. consumer cooperatives in developed economies) or truly marginalised communities (e.g. low-income workers). My framework doesn’t draw such distinctions. Many BCorps or companies embracing Shared Value will go well beyond what the table implies about their structure. This will not do them justice.

But the framework does help draw key distinctions in comparing the minimum in structural design required by these concepts. The differences are meaningful.

We should all applaud the narrative shift (and positive impacts) all of these ideas are driving. Equally, we need to compare and contrast the ideas that profess to fundamentally transform the business world. I hope this table helps achieve this.

Note to reader: I conducted this analysis in my personal capacity through October 2020 (while on paternity leave). To remain credible, I left out the Fair Trade Enterprise model (the global network I lead as Chief Executive of WFTO – see relevant report here and a talk about it here). Other ideas and concepts were also left out, where they lack concrete enterprise design features relevant to this comparison (e.g. Stakeholder Capitalism, Conscious Capitalism) or are broader concepts that capture multiple ideas (e.g. Fourth Sector/For-Benefit).

Erinch Sahan is Chief Executive of the World Fair Trade Organization. He has spent over a decade on enterprise development, campaigning for responsible business, lecturing on sustainability and researching new business models. His career spans Oxfam, Procter & Gamble and the Australian Government. He holds degrees in law and business, and an honorary Doctorate.

Connect with Erinch on Twitter: @ErinchSahan and on LinkedIn

Faces of the Wellbeing Economy Movement is a series highlighting the many informed voices from different specialisms, sectors, demographics, and geographies in the Wellbeing Economy movement. This series will share diverse insights into why a Wellbeing Economy is a desirable and viable goal and the new ways of addressing societal issues, to show us how to get there. This supports WEAll’s mission to move beyond criticisms of the current economic system, towards purposeful action to build a Wellbeing Economy.

the discussion?

Let us know what

you would like

to write about!